Enforcing design in the UK – easier than you might think?

Design rights are fast stepping out of the shadow of patents and trade marks as an important and versatile set of IP rights to businesses in almost all sectors. No longer seen as the preserve of the fashion, consumer and luxury goods industries, creating great product design and protecting it as a core business asset, is now widespread even in more tech-driven areas such as medical devices, engineering and aviation. Companies are investing in creating good product design because it matters more than ever before in an increasingly image-conscious world. Design is not just about how the product looks; it can also serve as a crucial indication of quality and brand origin.

Whilst companies from all sectors are undoubtedly starting to recognise the value and versatility of design rights, in the UK at least, a myth still persists in some quarters that design rights are harder to enforce successfully than other IP rights. There are perhaps two reasons for this misconception.

The first is that the four highest profile design cases in the UK in recent years (Procter & Gamble Co v Reckitt Benckiser, Apple v Samsung, Dyson v Vax, and PMS v Magmatic (Trunki)) have all resulted in findings of ‘valid but not infringed’. Trunki in particular, which went all the way to the Supreme Court, was widely publicised, and also widely criticised (albeit perhaps unfairly) for reaching the ‘wrong’ result. These four well known design cases, all with the same outcome, have undoubtedly lent weight to the perception that the English courts are reluctant to find infringement. However, as the broader statistics of recent design cases (discussed below) show, the outcomes of these four cases are not representative of the bigger picture.

The second reason is harder to discount. Generally speaking, the English courts have tended only to grant a relatively narrow scope of protection to design rights, meaning that the defendant’s product needs to be relatively close to infringe. The exact scope of protection to be afforded to a given design will of course depend on the facts, but only those designs without significant design freedom constraints and/or those which are radically different from the pre-existing design corpus will be afforded a wide scope of protection. Few designs can claim both. There may also be an unspoken rationale for the courts affording a relatively narrow scope of protection to design rights: registered EU and UK designs rights are granted without any substantive examination, without any proof of creation/entitlement, without any limitation to a field of use and without any requirement for the applicant even to use the design in question. In such circumstances, it is perhaps a reasonable quid pro quo that the scope of protection for such a right should be narrowly construed.

Narrowly construing the scope of protection does of course make it somewhat harder for the claimant to succeed on an infringement claim but, contrary to the popular misconception, the statistics of recent design cases from the English courts show that design owners more often than not are successful. Over the last 13 years, we have logged details of all judgments of which we have been aware which have been handed down by the English courts (IPEC, High Court, Court of Appeal or Supreme Court) in actions in which some form of design right (whether registered or unregistered and including artistic copyright relating to a physical product) was alleged to have been infringed. In total, we count there have been 35 such cases (but there are a greater number of judgments given that some of these cases have been appealed).

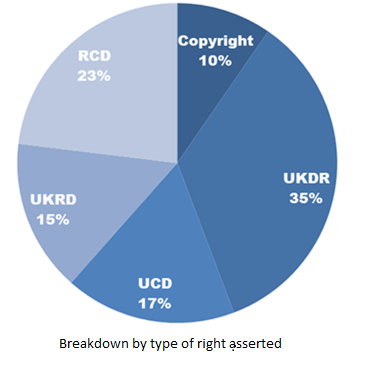

Which rights are being asserted?

As expected, in many cases, more than one type of right was asserted. Just under 40% were registered designs, compared to just over 60% unregistered rights, demonstrating the great importance which the unregistered designs regimes play.

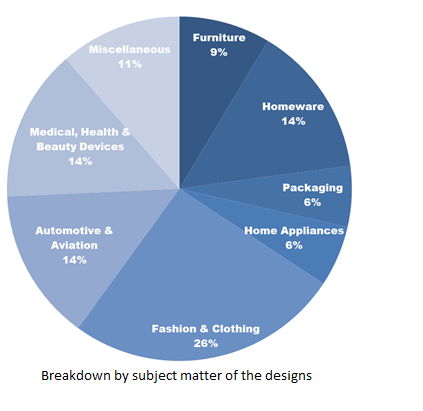

In which subject matter fields?

As one might expect, there is a strong showing for designs related to Fashion & Clothing and Homewares, but also a large number of designs relating to Medical, Health & Beauty Devices, and Automotive & Aviation, reflecting perhaps the increased recognition of the importance of design protection in these fields.

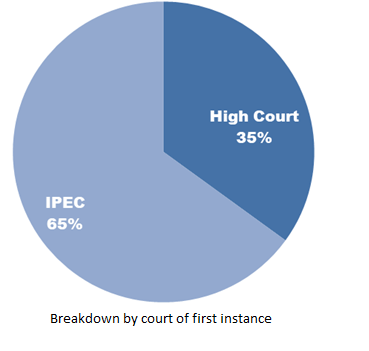

Before which court?

The statistics show that a significant majority of design cases are started in the IPEC. This may be attributed to the generally lower complexity and value of an average design infringement case, and/or the attraction of the IPEC cost cap to the parties. Perhaps more surprisingly, design cases brought in the IPEC appear to have had a noticeably higher success rate than those in the High Court (85% compared to 57%).

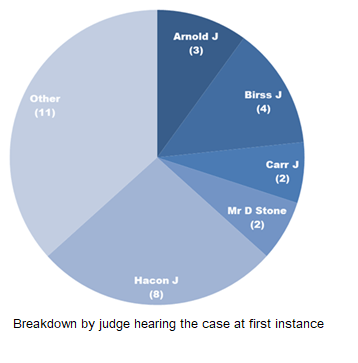

Before which judge?

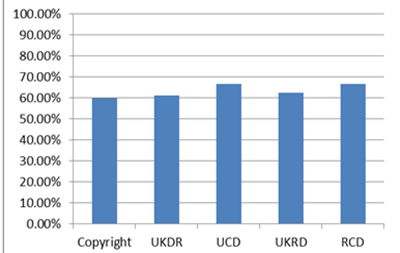

And the winner is…

Whilst not necessarily telling the full picture about the outcome of the case, we define ‘winning’ for present purposes as meaning that one or more of the rights asserted was found to be both valid and infringed. The average success rate (across all asserted rights) was 66%. The fact that two thirds of claimants succeeded in their claims should hopefully go some way to dispelling the myth that it is unduly difficult to succeed on design cases before the English courts.