IPEC rules on post-sale confusion in passing off and clarifies the scope of protection for movement under UK unregistered design law

In what could be a major decision for the fashion industry, last week David Stone (sitting as Deputy Judge of the Chancery Division) handed down judgment in Freddy SPA v Hugz Clothing Ltd & Ors [2020] EWHC 3032 (IPEC).

The decision is an interesting one not least because of its finding of passing off on the basis of post-sale, as well as point of sale, confusion, which has rarely been considered, but also its comments on how the scope of UK unregistered design protection encompasses the concept of movement. It also provides clarification that the shape of an article “when worn” by a human body is not a protectable design.

Background

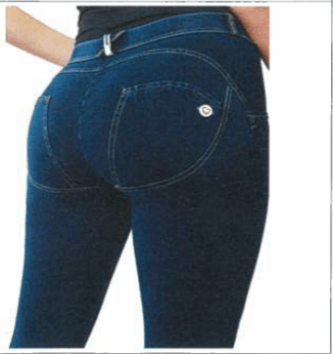

In 2012, Freddy SpA (“Freddy”) launched its ‘WR.UP’ branded “body-enhancing” jeans, said to “give the appearance of slimmer hips, whilst simultaneously lifting and separating the buttocks”, as shown below.

The Defendants (“Hugz”) admitted copying the WR.UP jeans and marketing their own ‘HUGZ’ branded jeans, as shown below, in respect of which they entered into a settlement agreement with Freddy.

Hugz then launched a second version of the HUGZ jeans (the only difference being the shortened curving false pocket seam, as shown below):

Freddy claimed that, in doing so, Hugz had:

- breached the settlement agreement;

- infringed its patent (EP (UK) 2 666 377 B1);

- passed off of the combination of branding elements at the rear of the jeans, shown above, including the metallic, pale gloss badge, a rear belt loop sewn at a 40 degree angle, two curved rear pockets and a scalloped rear yoke (the “Freddy Get-Up”); and

- infringed its various

UK unregistered design rights (“UKUDR”), including:

- the shape of the of the pair of jeans “when worn” (the “When Worn Design”); and

- the shape of the jeans without being worn, comprising the configuration of the various shaping panels, as shown above (the “JOTO Design”).

This article focuses on the judgment’s findings in relation to the passing off and UKUDR claims. There were also findings of breach of the settlement agreement and patent infringement, but these were more straightforward. As Hugz was unrepresented by the time of trial, Freddy’s expert evidence went unchallenged and it was held that the patent did not lack novelty, was not obvious and was infringed.

Passing off

The Judge was quick to find that Hugz had passed off the Freddy jeans in the conventional sense (i.e. attempting to create an association in the minds of consumers between the two brands).

More interesting was the Judge’s consideration of passing off in relation to post-sale confusion. This is the situation where a consumer knows that Hugz are unconnected to Freddy when buying the Hugz jeans, but buys them anyway, wanting other consumers to believe that their Hugz jeans are associated with Freddy and its jeans.

The Judge bore in mind that it was well-established in case law that such confusion is actionable as a matter of trade mark law, but in relation to passing office the question had rarely been considered. He referred to the High Court of New Zealand decision in Levi Strauss and Co and Anor v Kimbyr Investments Limited [1994] FLR 335, in which Williams J had found that Levi’s jeans, with its iconic red tab on the rear pocket, had been passed off by the defendant, which also used a red fabric tab on the rear pocket of its jeans, even though most purchasers would not themselves be confused at the time of purchase. There was a clear price differential between the jeans but this was not enough to dispel any misrepresentation: Williams J noted the attraction for some customers of buying a cheaper pair of jeans with a red tab which could be passed off as the plaintiffs’ jeans when worn.

The Judge followed this reasoning, finding that the owner of goodwill in a product is entitled to have this goodwill protected throughout the life of the product, not just at the point of sale. The expert evidence put forward for Freddy was that post-sale, customers would continue to make associations between Hugz and Freddy as a result of the get-up at the rear of the jeans, causing damage to Freddy. The Judge therefore concluded that there had been passing off on the basis of post-sale, as well as point-of-sale, misrepresentation.

This is a unique finding, whereby confusing post-sale use of similar aesthetic design elements on an article of clothing (as opposed to trade marks, such as brand names or logos) can be used as a basis for passing off. As such, this line of argument is likely to be of great importance to designers of consumer goods which are often viewed from afar, such as fashion items. It might be argued that there is less public interest in allowing post-sale confusion in passing off claims, as unlike for confusion at the point-of-sale, where consumer protection interests as well as brand owners’ interests are concerned, post-sale confusion can be said to be of concern to brand owners only. However, such concern to brand owners is likely to be considerable. Consider the situation where the circumstances of sale reduce the possibility of confusion at the point of sale (for example, the product in question has a different logo/brand name that is only noticeable up close, or a disclaimer is used, or there is a clear price differential) but later, when the lookalike product with similar branding elements is worn without those circumstances or that context, it is no longer readily distinguishable from the brand owners. This can reduce the ability of a brand to guarantee the origin of its goods, and lead to lost sales and the devaluation of the brand.

UKUDRs – Definitional issues

Is a design “when worn” a protectable design?

In its defence, Hugz claimed that the When Worn Design was not protectable as “the design is not the shape or configuration of an article as such, but the shape and configuration adopted by an article as produced where worn by a particular individual”. Freddy’s evidence that the resultant design was predictable was only accepted in so far as when it was worn, the wearers’ buttocks would in each case be lifted and separated. The Judge held that even within a range of body shapes that would fit a given size of jeans, there will be a significant variation in body shapes, and as such, significant variation in the resultant shapes of the jeans “when worn”. The design was held to be invalid.

What about the JOTO design – does ‘configuration’ allow for consideration of an article’s movement?

With the JOTO design, Freddy relied on “the shape and configuration of the WR.UP jeans themselves on their own, such configuration to include the elastic nature of the fabrics and materials making up the WR.UP jeans” (emphasis added). The issue was therefore whether “configuration” allows for any consideration of the movement of an article.

The Judge highlighted that the notion of shape and configuration in UKUDR law is a broad one, and therefore should encompass the concept of movement. He pointed to examples of articles that had been capable of being moved in the case law, such as the umbrella in A Fulton Co Limited v Grant Barnett and Co Limited [2001] RPC 16. He concluded that the elastic nature of the fabrics and material constituted the shape and/or configuration of an article, and so was protectable as defined.

Were the UKUDRs excluded from protection?

Hugz advanced several objections against the various UKUDRs, all of which were rejected by the Judge. Perhaps the most interesting was the ‘must match’ objection levelled at the When Worn Design, under section 213(3)(b)(ii) of the CDPA, on the basis that the shape of the jeans when worn was dependant on the appearance of another article (namely the human form) of which the jeans are intended by the designer to form an integral part. The Judge did not conclusively determine the preliminary question of whether the human body can be considered to be an “article”, but rejected this objection on the basis that even if it was, there is no integration of the jeans with the human body to form a single article.

Was there infringement of the UKUDRs?

As the second Hugz jeans were found to have been made substantially or exactly to the valid UKUDRs, these were all found to be infringed. Had the When Worn Design been valid, it would also have been infringed.

Conclusion

This judgment’s line of argument in relation to passing off could be of major significance to the fashion industry, which often relies heavily on the recognition of branding elements on their products by potential customers, but which branding elements are habitually the victim of counterfeiting. If post-sale confusion can now be relied on in passing off claims, fashion designers will have an additional tool in the fight against these copycats. Extending passing off to include post-sale confusion would close the gap between trade mark law and passing off, and ensure that the purpose of the tort cannot be subverted by the mere use of a disclaimer, or other circumstances, to remove confusion at the point-of-sale even though confusion might, or is even intended to occur, post-sale. The decision also provides useful guidance on the issues that can arise when the design of an article is defined by reference to the shape of the human body.