Problems with protecting the design of ‘next generation’ products in a design family

Many commercially successful products undergo regular design (and technical) refreshes to ensure that the product changes with the times and remains relevant and interesting to consumers, whilst retaining the pulling power of the product identity. A classic example of this would be the Apple iPhone which has been reincarnated in numerous different ‘generations’ since it first launched in 2007. Designers may however encounter difficulties when seeking protection for re-vamped, ‘next generation’ designs within a particular design family, as Porsche has recently found out (Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG v European Union Intellectual Property Office, Case T-209/18). On the one hand, the next generation design usually needs to be sufficiently similar to its predecessors to be readily identifiable as sharing the particular design ‘DNA’ of the family. On the other hand, it needs to be sufficiently different to have individual character over those predecessor designs to allow it to be validly registered.

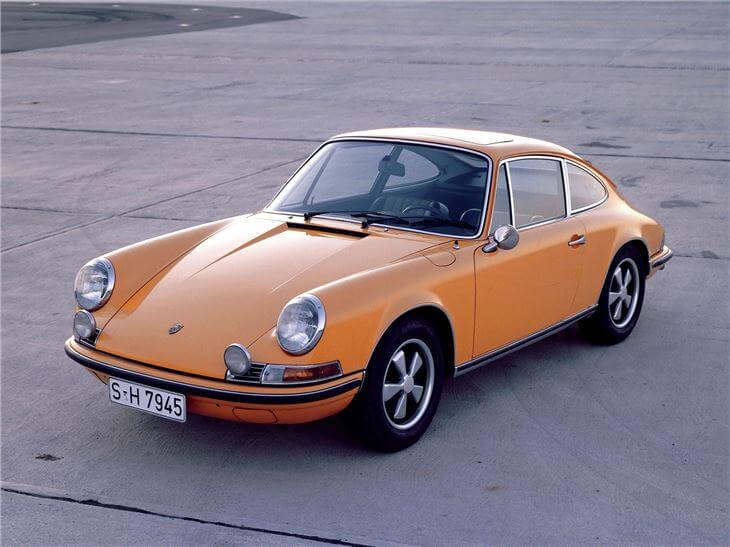

Since its launch in 1963, the Porsche 911 has been one of Porsche’s most popular models. While the 911 has been upgraded over the years, its iconic look and feel has been maintained. However, from a design perspective, protecting its distinctive identity over successive generations can pose certain obstacles.

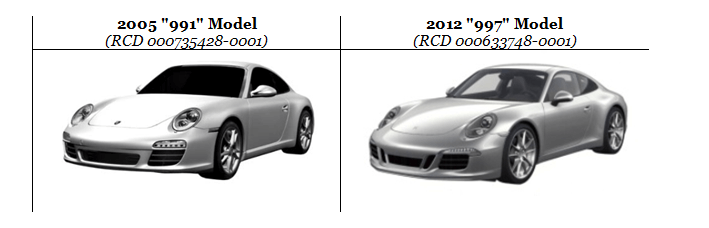

In 2012, Porsche registered design number RCD 000633748-0001 (below right) to protect the design of the then latest version of the 911. Autec AG, a German toy company, successfully challenged the validity of that RCD before the EUIPO on the basis that it lacked novelty and individual character over an earlier RCD also belonging to Porsche (RCD 000735428-0001)protecting the design of the 2005 version of the 911.

Following an unsuccessful appeal to the EUIPO Third Board of Appeal, Porsche appealed to the General Court. In the General Court’s judgment upholding the finding of invalidity, three interesting points emerged in particular:

- Who is the “informed user” here?;

- How is “design freedom” interpreted?; and

- How to assess “individual character”?

The informed user

To determine whether a design has individual character (as required by Art. 6 of the Community Designs Regulation), one must consider whether the overall impression it produces on the informed user is different to that produced by any design previously disclosed to the public.

Porsche argued that the EUIPO erred by defining the informed user as the user of cars in general; as opposed to just “sports cars” or “Porsches”. The General Court rejected Porsche’s arguments on the basis that when defining the informed user, consideration must be given to the scope of goods to which the design applies, taking into consideration the application and the design itself. In the absence any other indication that the design’s scope was limited, because Porsche had registered the design under Locarno class 12.08 (“automobiles, buses and trucks”), the EUIPO was correct in its broad interpretation of the relevant goods.

Design freedom

In determining whether a design has individual character, consideration must be given to the design freedom available to the creator. Where design freedom is limited (e.g. due to technical or legal limitation), smaller variations between designs may suffice to create a different overall impression.

On this basis, Porsche argued that design freedom was limited by its customers’ expectation that the Porsche 911 will maintain its unique and original design identity. However, the General Court again disagreed, finding that design freedom must be assessed for the product category (e.g. cars), and not that of any particular product within that category. As such, meeting consumer expectations of a particular product could not be regarded as a factor limiting design freedom.

Individual character

Porsche also argued that, when assessing individual character, the EUIPO failed to take into consideration the additional materials attached to the registration (i.e. advertisements and photographs) and the peculiar shopping behaviour of a 911 buyer who, Porsche claimed, will pay attention to even minimal differences between the models.

The General Court rejected Porsche’s argument and reiterated the well-established principle from case law that when examining individual character, one must compare the overall impression produced by the contested design against that produced by the earlier design. In doing so, no consideration should be given to any excluded characteristic (i.e. features not identified in the design itself).

Commentary

This case demonstrates the difficulties which designers may encounter when seeking protection for re-vamped, ‘next generation’ designs within a particular design family. In this case, all is perhaps not lost for Porsche. Whilst it may no longer have registered design protection for its 2012 version of the 911, it still has registered design protection for the 2005 version. Given that the 2005 design was deemed sufficiently close to the 2012 design to invalidate it, it should follow that it would also be close enough to any copy of the 2012 design to be a useful weapon should it be needed in any enforcement action.